As Buffalo and surrounding communities continue to debate the future of intrusive urban freeways, foremost the Scajaquada Expressway, Buffalo Rising examines some of the historical design principles behind Buffalo’s pioneering Olmsted park and parkway system. “The way we invoke the name of Frederick Law Olmsted around here, you would think that he and his partner, Calvert Vaux, brought forth landscape architecture and park design as a kind of received wisdom from on high,” writes contributor RaChaCha. “And perhaps rightly so. But while we should take their principles very seriously, they are received wisdom only in the sense of being derived from nature, and especially from human nature.” “In the award-winning book The Park and the People, Elizabeth Blackmar and Roy Rosenzweig tell the story of how the principle of ‘separation of ways was not in the dynamic duo’s original ‘Greensward’ plan [for New York’s Central Park], but rather was suggested by a park commissioner.” “Olmsted and Vaux, to their credit, embraced this idea and made it their own. It helped that the idea was an extension of their own novel system of grade separations and overpasses to handle the four transverse roads that the City of New York required to traverse the park. That feature was included in the original Greensward plan, and has been credited with winning them the competition. As a 1982 New York Times article put it, ‘[Olmsted and Vaux] won because they had been able to solve the tricky problem of what to do with traffic crossing the park. Their plan for the sinking of the transverse roads allowing traffic to pass through with minimum intrusion was unprecedented in city planning.'” “But they also took the commissioner’s further than he imagined by also introducing a third way to experience the park: on horseback, on bridle paths. Thus was born the Olmstedian principle of the ‘separation of ways’ within parks. You can see these same principles in operation in the design of Delaware Park. Despite alterations and obliterations over time—many thanks to construction of the 198 [Scajaquada Expressway]—you can still find remnants of the original carriage drives and bridle paths.” “This system of keeping the three means of moving through the park separated, and also keeping the park separated from the transverse roads, gave birth to the many bridges that are a beloved feature of Central Park. Vaux, an architect by training, and other architects and artists lavished attention on them. And the next park Olmsted and Vaux cooperated on, Prospect Park, was designed around this concept from the beginning and took it to what is considered its highest level. In Prospect Park, many of the bridges would also serve almost as the frames of great landscape paintings, or portals through which a city dweller could enter another world—whether by foot, on horseback, or in a carriage.” “Sadly, except for the Ivy Arch on the former Rumsey Tract in Delaware Park (and perhaps the buried bridges at the quarry), Buffalo’s Olmsted parks are bereft of such path separation bridges.” “That leaves us with the question: is it possible to design a road that traverses this Olmstedian landscape, and the lower Scajaquada Creek corridor, using Olmstedian design principles? I think it is, and will be writing more to lay out one possible solution.”

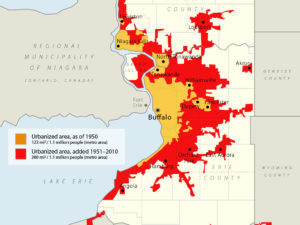

In Buffalo's Delaware Park, at Delaware Avenue, Olmsted adapted the natural slope of the Scajaquada Creek valley to put the park over the road on a stone-arch bridge. (Image credit: Buffalo Rising)

In Buffalo's Delaware Park, at Delaware Avenue, Olmsted adapted the natural slope of the Scajaquada Creek valley to put the park over the road on a stone-arch bridge. (Image credit: Buffalo Rising)

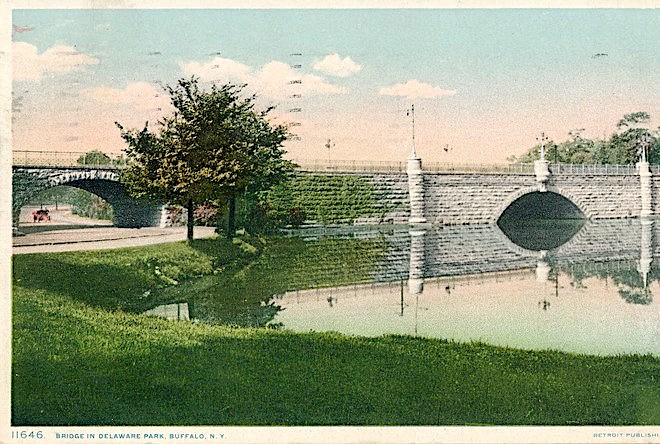

At Elmwood Avenue in Delaware Park, Olmsted and Vaux put the street high across the creek valley on a stone causeway, with an arch underneath for a carriage drive to extend west along the creek. (Image credit: Buffalo Rising)

At Elmwood Avenue in Delaware Park, Olmsted and Vaux put the street high across the creek valley on a stone causeway, with an arch underneath for a carriage drive to extend west along the creek. (Image credit: Buffalo Rising)