“It’s pretty easy to destroy a walkable place. We’ve been doing it for so long, it’s almost second nature,” writes Sarah Kobos for Strong Towns. “First, prioritize auto travel. Require every new building to be surrounded by lots of parking; and require every new street to be designed for high-volume, fast-moving traffic. Second, designate separate areas for people to live, work, and shop, and don’t allow any of these ‘uses’ to mingle. Third…. Well, actually, the first two will do it.” “I could go on. We could talk about over-zealous fire marshals, outdated subdivision regulations that recommend cul-de-sacs instead of connected streets, federal policies that prioritize single-family suburban homes over mixed-use buildings, and inadequate transit systems. We could certainly talk about redlined neighborhoods, the Interstate Highway Act, and urban ‘renewal’—policies that transformed American cities like the Allied bombers transformed Dresden.” “But let’s keep it simple. Over decades—one parcel and one building at a time—we have created new places where it’s virtually impossible to survive without a car, while systematically chipping away at the older places that used to be fully functioning, walkable, high-yield neighborhoods. Little by little, these once thriving areas have been degraded until they no longer work for people on foot.” “OK, so mistakes were made, as the politicians like to say.” “I can almost forgive the mistakes of the past. (Well, not all of them. The more I learn about the history of federal housing policy, the more it makes my head explode. I also retroactively hate everyone responsible for demolishing architectural treasures because someone wanted more parking or a building made of precast concrete. For the perpetrators of these crimes, I’m going to hold a grudge.)” “But I really do believe that most people had good intentions and acted in good faith. I’m sure that for the past 70 years, most civil engineers, city planners and members of local planning commissions thought they were doing the right thing to make their cities better. All that ‘shiny and new’ stuff probably looked pretty good at the time.” “Fine. We’ll add the suburban development pattern to the long list of humanity’s mistakes that occurred during the latter half of the 20th century. Like feathered bangs, the Ford Pinto, or any tattoo you got before the age of 35, sometimes we err, not because of malice, but from an understandable combination of ignorance and exuberance.” “The thing that really drives me crazy is the present. Now, we know better. We recognize the economic, human health, and environmental benefits of traditional building patterns. And yet, there is so much inertia built into the system, we just keep building car-centric crap like it was 1985.” “Here’s the conundrum: it’s incredibly hard to insert walkable places into an auto-centric landscape. In areas defined by fast cars, wide streets, large lots, single-use zoning, and inhospitable asphalt blast furnaces, you can’t just build a nice storefront up by the sidewalk and expect it to succeed. Your otherwise perfect design will fail as a walkable place because of everything that surrounds it. Good luck trying to grow a fern on a sand dune in the Sahara.” “But you can all too easily insert a car-centric development into a walkable area with no negative consequences (to you). Your single-use, suburban-style development will function as designed—for people in cars—operating independently from everything around it. Meanwhile, that single inappropriate project will degrade everything else in the surrounding ecosystem that makes the place desirable to begin with. It will increase auto traffic while disrupting the urban fabric and acting as a barrier to people on foot.” “In older parts of the city, walkable neighborhoods are being rediscovered and revitalized because they’re interesting, human-scaled, and pleasant. People are drawn to them because they have character, and because it’s nice to be able to walk to dinner or bike to meet friends for coffee. Understandably, the moment a particular neighborhood becomes popular—thanks to its historic buildings and traditional building pattern—it will attract new development. But if you’re not prepared with zoning laws to enhance and support walkability, you’ll get what everyone knows how to build, which is crap for cars.” Western New York is helping lead the nation in reversing the erosion of traditional, walkable neighborhoods by incompatible suburban development. Recent local zoning updates are designed to prevent just this sort of thing, most notably the Buffalo GreenCode, as well as new zoning for the villages of Hamburg, Williamsville, East Aurora, and the City of Olean. — Ed.

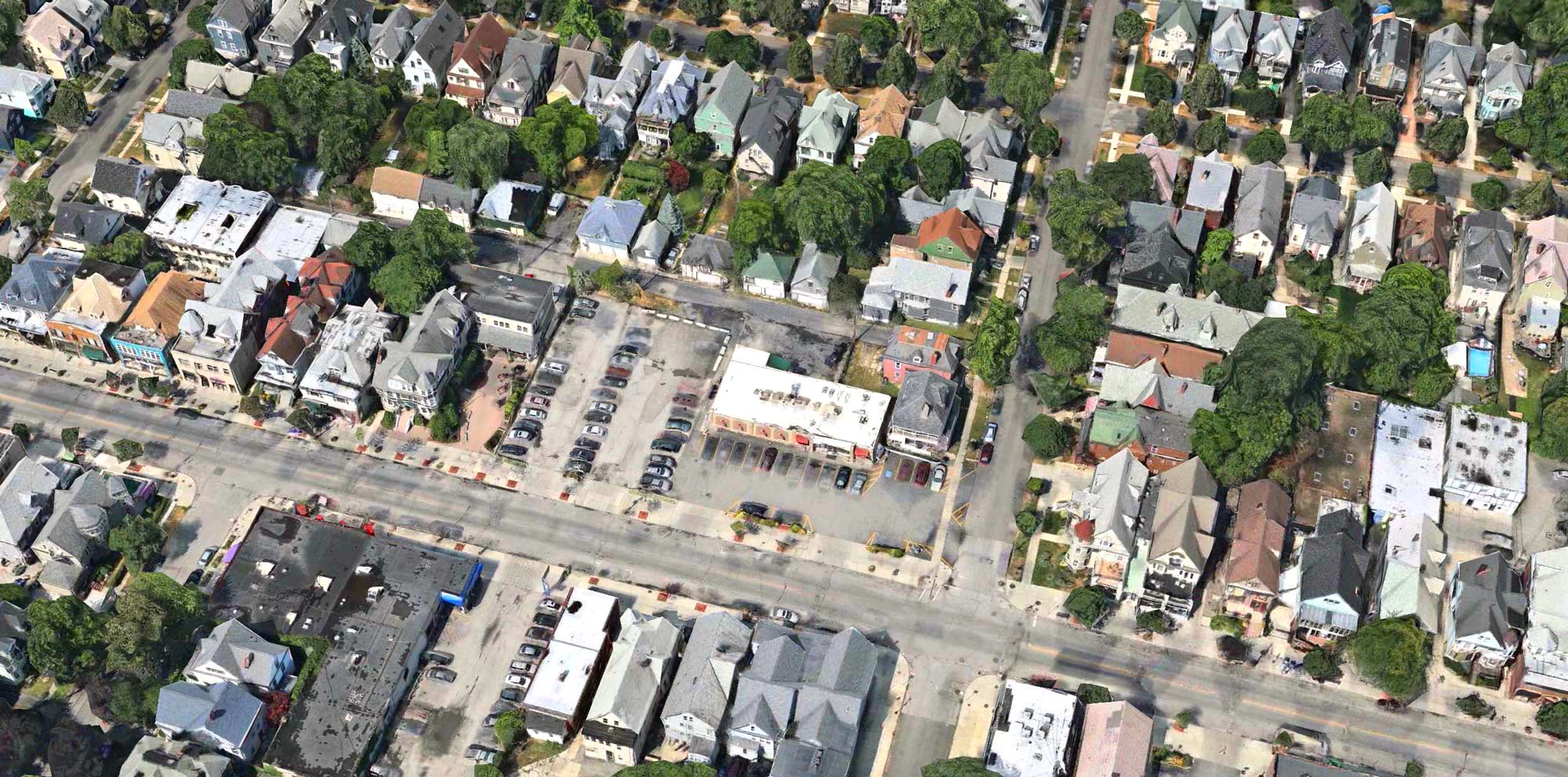

Cul-de-sacs, drive-thrus, and surface parking lots are NOT what this neighborhood needs. Incidentally, recent local zoning updates are designed to prevent just this sort of incompatible development, most notably the Buffalo GreenCode, as well as new zoning for the villages of Hamburg, Williamsville, East Aurora, and the City of Olean. (Image credit: Apple Maps)

Cul-de-sacs, drive-thrus, and surface parking lots are NOT what this neighborhood needs. Incidentally, recent local zoning updates are designed to prevent just this sort of incompatible development, most notably the Buffalo GreenCode, as well as new zoning for the villages of Hamburg, Williamsville, East Aurora, and the City of Olean. (Image credit: Apple Maps)